High Noon at Stadtgalerie Kiel

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Mary and Babe, N.Y., 1982, New York 1982. Chromogenic Color Print. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Courtesy of the artist, Sprüth Magers and David Zwirner.

High Noon: Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Mark Morrisroe and Philip-Lorca diCorcia

Stadtgalerie Kiel

June 14th - August 31st

I spent the last two weeks of my summer vacation working on a boat going back and forth between Oslo and Kiel. In the high season of family holidays, days were long and tiresome, with little time to truly digest the many impressions I was left with. As the boat docked in Kiel on a cloudy morning in late July, I decided to spend my daily break in a quiet place, wandering alone in Stadtgalerie Kiel. Behind sound isolating glass doors, the nearly empty main gallery showing High Noon provided a comforting pocket of light and air. Here, bathed in cool light and the soft hum of air conditioning, photographs by Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Mark Morrisroe and Philip-Lorca diCorcia covered the otherwise white walls.

In the introduction to the exhibition, Sabine Schnakenberg writes of high noon being the time of day where the sun is at its highest, leaving no shadows.[1] The stillness of such a moment, when nothing is hidden, dramatized or enhanced by the presence of a dark shadow, strangely resembles the temporal vacuum created by the brightly lit, windowless gallery. The exhibition's stillness is further accentuated by the artistic format shown; the photograph.

Nan Goldin, Nan And Brian In Bed, New York City, 1983. Cibachrome, 50,8 x 61 cm. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © Nan Goldin, Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

Whether it is Nan Goldin's snapshots providing us with unique, fleeting glimpses into a moment long passed, or the exhibitions more carefully orchestrated photographic compositions staring boldly back at us from a place strangely devoid of time, one gets the feeling that the clock has stopped. In the case of The Boston School - an expression used loosely to frame the selection of artists present in this exhibition - one also gets the feeling that the clock is stopped on purpose. That something or someone present in the dark night clubs, overflowing dressing room tables, unmade beds and crowded streets is being captured in order for them to follow along into a future they were not destined for. This milieu, characterized by the urban drug, sex and music scene of the American 70s, 80s and 90s, is what becomes a defining outline of the show. Rather than being a tight knit group holding shared artistic interests and philosophy, the four artists showcased are linked by their shared place of education - namely the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston - and their documentation of a culture that in some way or another changed beyond recognition at the hand of the AIDS epidemic and postmodern gentrification.

David Armstrong, Cookie at Bleecker Street, New York, 1977. Silbergelatine. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © Courtesy of the Estate of David Armstrong.

Like cryofrozen astronauts, the people photographed are carried onward into the future by the medium they are captured in. The prints thus become space ships and time machines, holding the frozen hearts of people alive as they are transported into a world which is safer than the one they arrive from. As my eyes meet the gaze of Cookie Mueller, the long time friend of Nan Goldin who passed away from AIDS in 1989, it is like looking into the window of such a space ship. There is a strange uncanny feeling to it. Blonde perms, pale flowery wallpapers and indoor smoking are all things I think of in relation to fuzzy, sun bleached family photos of my parents and grandparents in their younger days. Looking at Cookie, I do not get the same feeling of time passed. I stand before her as if in front of a hole in the wall, looking directly at the past as it too looks backwards.

Looking into a camera is a strange way of floating between past and future. Allowing your portrait to be taken is a kind of reconciliation between the fear of death and the dream of immortality. By being captured on film, you accept becoming glued to the past in order to be transported into the future. You accept immediate death for the sake of eternal life. The version of Cookie Mueller that left a mark on David Armstrong's film roll in 1977, will survive like the shoe of Neil Armstrong on the moon; through its imprint on a surface where the winds don't blow. Thus, it is strange to follow the exhibition inwards and end up in front of Nan Goldin's photograph of Cookie in her casket. Even there, she lives on. Just as still, she lies down dead as she stands up dancing just a few pictures back. As Roland Barthes writes in his Camera Lucida; “the photograph tells me death in the future…Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.”[2] The photo of Cookie pissing in the dirty bathroom of a night club is thus just as much a carrier of the message of her death as the photo of her prepared for burial. Looking at the dead Cookie Mueller, I felt as if a visual story unfolding in front of me had ended abruptly, mid sentence. I was left with the echoes of Goldin's colorful party scenes blending with the strong sound of the large fan blowing synthetic winds throughout the gallery room, before disappearing completely into empty space.

Nan Goldin, Jimmy Paulette And Tabboo! In The Bathroom, New York City, 1991. Cibachrome, 76,2 x 101,6 cm. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © Nan Goldin, Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

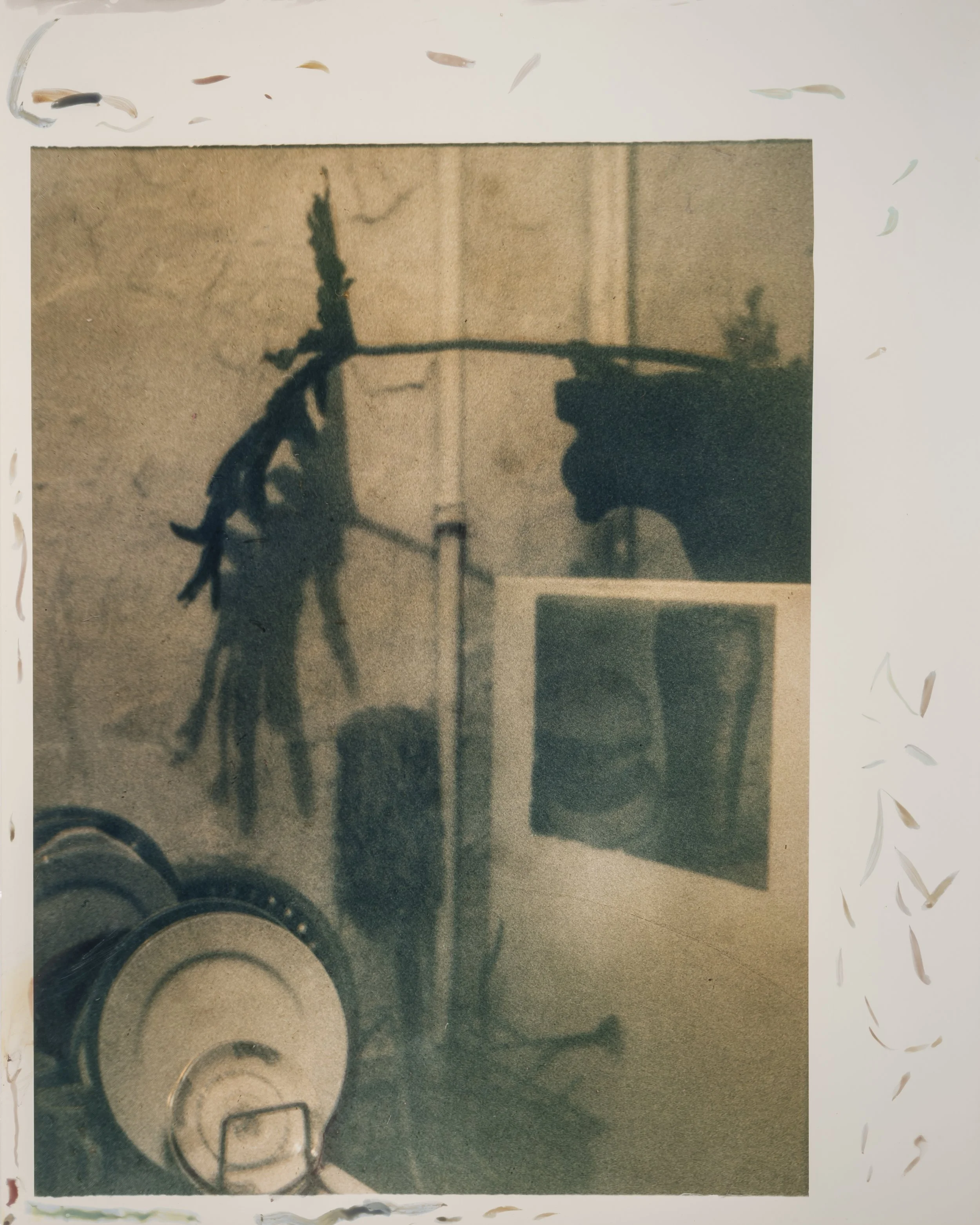

Life is not a necessary component of a photograph, but death is, and it looms over the exhibition. Goldin's photos show wedding beds, hospital beds and death beds. Armstrong's large black and white prints show fuzzy images of empty streets, and portraits of people draped in a monochrome melancholy. Morrisroe's dark, murky images evoke mental images of a truth I learned from reading crime novels as a child; that death smells disgustingly sweet. As if oozing with a heat from the rich soil of decomposing life, his images have a warmth and depth that is as alluring as it is unsettling. Like looking into a deep well, one is pulled towards the center of a mysterious darkness.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Major Tom, Kansas City, Kansas, $20, Kansas City 1990/1992. Chromogenic Color Print. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg.

As for Philip-Lorca diCorcia, death is not immediately apparent in his theatrically lit photographs of street life. Fittingly, his images are also placed in a room slightly separate from the other artists. This does not only mark a thematic difference between diCorcia and his peers, but is also a way of showing respect to the artist's own aversion to the narrative of there even being a «Boston School». In his words, the «drug and funny-sex world» of Boston was the main thing that the group, later referred to as The Boston school, had in common.[3] Where the other artists in the exhibition approach these subjects with an intimate and personal eye, diCorcia rather focuses on constructing archetypes of the people and situations from his daily life. The crowded streets, lonely hearts and tragic destinies of the urban metropole are shown as cinematic frames, alluding to greater narratives. The sharp photographs appear as more clearly articulated sentences than the fuzzy, fleeting and fragile photos of the remaining Boston School. Still, the greater story is left unsaid. This makes the individual artworks stand out as single frames from movies that don't exist.

Mark Morrisroe, Untitled [John S. and Jonathan] 1985. Color Print von Sandwich-Negativ. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe.

The works of Mark Morrisroe also possess this quality, but where diCorcia plays with conventions from Hollywood, Morrisroe's shots are reminiscent of home movies. Dark, grainy and out of focus, they seem like documentation of the private, rather than an orchestrated public. As two lovers embrace in the warm light of a windowless room, their movements are captured in the fuzzy outline of their bodies, giving their skin a luminous glow. Fleeting and faceless, they are not archetypes, but sanctified individuals. Experimental techniques, involving cut outs, handwriting and layering, give a material quality to these images. If Goldin's pictures are windows to spaceships from the remote worlds of the 80s party scene, Morrisroe's pictures are the rough fossils of the same era. No clear glass, no direct eye contact. Just the material imprints of love in the hardened mud. The grainy fields where naked skin dissolve into complete darkness in Morrisroe's photos, are like the visual version of feeling the warmth of a loved one in the dark.

Mark Morrisroe, Untitled [Sweet Raspberry/Lady Madonna], 1986. Color Print. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe.

Mark Morrisroe, Untitled, ca. 1987. Color Print von Sandwich-Negativ. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe.

Mark Morrisroe and Nan Goldin share a trait that makes their photographs appear as parts of the same world. That world is the windowless, electrically lit underworld of a town whose exterior is gradually being transformed by a cold and cynical postmodernity. In these bunker-like interiors, cultural symbols, vintage furniture and fabulous fabrics seem preserved from destruction. Jumbled together with the cultural objects of a fading age of glamour, the party goers and lovers seem to be hiding from a harsh wind blowing on the outside the cracked brick walls. As if already archived into a subterranean library of life, the lovers, friends and strangers in these images greet the flash of the camera like a ray of sunlight. Like they are looking out of the hiding spot of a subcultural meeting place, a night club backstage, a living room with the curtains shut, and into the bright and unapologetic light of the outside world.

David Armstrong, Andrew at Battery Park, New York City, 1994. Silbergelatine. Haus der Photographie/Sammlung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg © Courtesy of the Estate of David Armstrong.

But you also have the people immortalising the outside of these hidden corridors. David Armstrong partakes in the exhibition with a series of portraits showing ponderous people draped in the shadows of branches and leaves, far from the physical urban underground. Philip-Lorca diCorcia captures the bustling streets, empty parking lots, sun lit living rooms of an America lacking warmth and human connection. This contrasts the air tight time capsules from the beating heart of the American underground with its colder exterior. Its black and white melancholy, its decaying suburbia. This is the America that would later seep into the spaces beneath it, as it failed to tackle the destruction brought upon the underground cultural scene by the AIDS epidemic.

Like the sun at zenith at high noon, the Boston School too seems to have been in just about the right place, at the right time, to accurately cast light upon the world they existed in. With a precise amount of distance from the objects they were framing - that is to say; very little - they seem to have grasped the ghost of a time passing at extraordinary speed. Looking at these photographs as a young norwegian art student wandering in a german gallery, felt like reading a story of a lost American utopia. A hidden forefront against forces seeking to eliminate cultural deviation and political subversion, that suffered at the hand of capitalist agenda and physical illness. I came to reflect upon the possibilities for such a scene today, and furthermore, the possibilities of documenting it in such a manner. It seems to me like the naive use of photography to immortalise one's surroundings has slowly disappeared in the transition to the digital age. With cameras and photographic images being such a big part of our day to day life, from selfies to news reports, it seems to me like the very notion of the photograph piece of history has slowly dwindled. And in the way they haven't, it is as the journalistic report, documenting rather than merging with the milieu it is capturing. [1] [2] The flash of celebrity photographers, paparazzi and professional cameramen has turned the photo into evidence, rather than historical artifact. With a stronger bond to the narrative of reality, than to the fiction of history.

If it is true that the “drug and funny sex scene” was the characterizing trait of the Boston School, one could argue that this exhibition balances its core forces with its strict counterparts. Drug induced ecstasy with mournful sobriety. Warm dirt with cold plastic. Sex and love with isolation and death. Whatever made the soil of this era in American photography so fruitful, in the end does not matter. The photos' greatness and reason all lie in the light and time unifying behind the closed shutter of a camera, immortalising the high noon.

Literature:

[1] Sabine Schnakenberg. “Introduction” in exhibition catalogue for High Noon at Stadtgalerie Kiel (Kiel: Stadtgalerie Kiel, 2025), 5.

[2] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1982), 96

[3] Manuel Segade (ed.) Exhibition catalogue for Familiar Feelings. On The Boston Group at Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea (CGAC) (Santiago de Compostela: CGAC, 2009), 235.